The SEND system in England is at “breaking point”. We need to move towards an effective and financially sustainable approach to inclusion and additional needs in England

It is ironic that we have spent the past year working on a project on the future of the “SEND system” in England only to reach the conclusion that we should stop talking about SEND as a “system”, separate from the wider education system. That is, nevertheless, our fundamental conclusion – that we should pivot away from a system that forces practitioners and families to seek separate assessments, plans, funding and entitlements for children and young people who need additional support, and towards a more inclusive conception of education and child development.

This work, which has spanned the 2023/24 academic year, was commissioned by the Local Government Association and the County Councils Network for this precise moment in time. The general election offers an opportunity to rethink, reimagine and reset our approach to education and, within that, how we recognise, value and support children and young people with additional needs. Through this work, we have drawn on the views of leaders involved in what is currently called the “SEND system” – young people, parents and carers, leaders of early years settings, schools, colleges, health services and local authorities (LAs). In the report that has just been published, we argue that:

the current system is broken;

this is due to a perfect storm of three inter-related factors;

reform is therefore essential and unavoidable;

a future system must put the principles of inclusion and preparation for adulthood at its heart.

The current system is broken

Given the broad range of people who contributed to this research – young people, parents and carers, educators, health practitioners, LA officers – it was striking how many used the same term to describe the current system: “broken.” In 2018, we argued that the SEND system in England was at a “tipping point”. Six years later, the evidence points to the fact the system has reached breaking point.

When people describe the current SEND system as broken, they are essentially referring to four key facts – summarised here and evidenced in detail in our report.

1. More children and young people than ever before are being identified as having SEND – this can be seen most starkly in the rise in statutory Education, Health and Care Plans (or EHCPs, up 140% since the 2014 SEND reforms). Among pupils in schools, while the overall school population has risen 6%, the number of pupils with EHCPS has risen 83% and the number of pupils on non-statutory SEN Support has risen 25%. The growth in identification of SEND is a nationwide phenomenon – 90% of LAs in England have seen a doubling (or more) of the numbers of EHCPs.

2. There are more children and young people with SEND whose needs are not being met in mainstream education and are requiring specialist provision – placements in state-funded special schools have risen 60% in the decade since the reforms, while placements in independent and non-maintained special schools have risen 132%.

3. More money than ever before is being invested in the SEND system … but it is not keeping pace with what is actually being spent. Despite increased investment in high needs funding, the in-year deficit (£890 million this year, projected to grow to £1.3 billion by 2025-26) and the national deficit (£300 million in 2018-19, now £3.16 billion) are growing. While these pressures also affect the budgets of education settings and health services (but are more difficult to measure), the threat posed by the high needs deficit to local government is existential – half of the LAs in England said they would be insolvent within three years if the so-called statutory override was removed and LAs had to hold the deficit on their books.

These three facts might be justified as the necessary cost of improving the system were it not for the fourth fact…

4. Outcomes for children and young people with SEND have not improved, and on some measures have got worse – despite ever-increasing identification and statutory assessments, specialist provision and investment of public funds, outcomes for children and young people with SEND have at best flatlined and at worst declined. This can be seen in academic, destination, employment and health outcomes for young people, and the increase in the numbers and rates of Tribunal appeals. The statistic that best encapsulates the failure of the current system to improve outcomes is that a young person with an EHCP who turned 19 in 2022/23 (and completed the bulk of their education under the current system) is less likely to achieve a Level 2 qualification at 16, 17, 18 and 19 than their counterparts who turned 19 in 2015/16 (and completed the bulk of their education before the 2014 SEND reforms were introduced).

These challenges are caused by a “perfect storm” of three inter-related factors

1. First, there is a challenge of “volume” – the system is struggling to respond to the ever-increasing volume. In our report, we argue that this is being driven by both increasing complexity of need and a crisis of demand, where existing needs are not always being met at the right time.

2. Second, there is a challenge around “decision-making” – in most areas of public service, the state is able to clearly set out a core and equitable offer for its citizens. A range of weaknesses within the current statutory framework for SEND (including a lack of clarity about how we define SEN and the tests for statutory assessment, misalignment of responsibilities and accountabilities, and the role of the Tribunal) make it difficult for the state set out a clear, consistent and equitable offer of special education, which in turn exacerbates the volume challenge.

3. Third, there is a “market” challenge – specifically that the operation of the independent market within the SEND system is both a symptom and a compounding factor of the other two challenges.

Reform is essential and unavoidable

The issue is not that central government have underfunded the system that the 2014 reforms created. In fact, the previous government’s strategy from 2018 was to increase funding while leaving the system unreformed. In the three years prior to 2018-19, EHCPs rose 36%. In the three years after 2018-19, government responded by increasing high needs funding by 40%. The result? The increase in EHCPs continued unabated (33%). For this reason, we argue that reform is essential and unavoidable. Without reform of the whole system – including national policy and the current statutory framework – we will simply have a system with the same problems, but ever greater costs (not just in financial terms, but in terms of lost opportunities for children and young people).

In our report, we focus on national policy that relates directly (e.g. the SEND statutory framework) and indirectly (e.g. the wider education system and services for families). We do so because we do not consider that the issues in the current system are the result of any one group acting unreasonably – we are at pains to avoid apportioning blame to families for wanting what is best for their children, or to practitioners for striving to be inclusive and meet needs in a system that has made that increasingly difficult.

A future system that is effective and sustainable must place the principles of inclusion and preparation for adulthood at its heart

In our report we set out a broad and comprehensive blueprint for reform. We recognise that there will be different views about how to achieve reform of the current system. Our report is intended to show what whole-system reform could look like and how it could be accomplished. If our proposals were taken up, they would need to be explored further by stakeholders to develop a detailed plan for implementation. What is essential is that any future reform needs to be broad in its ambition and holistic in its approach – our recommendations are designed to fit together to effect whole-system change, rather than be a “pick-and-mix” menu.

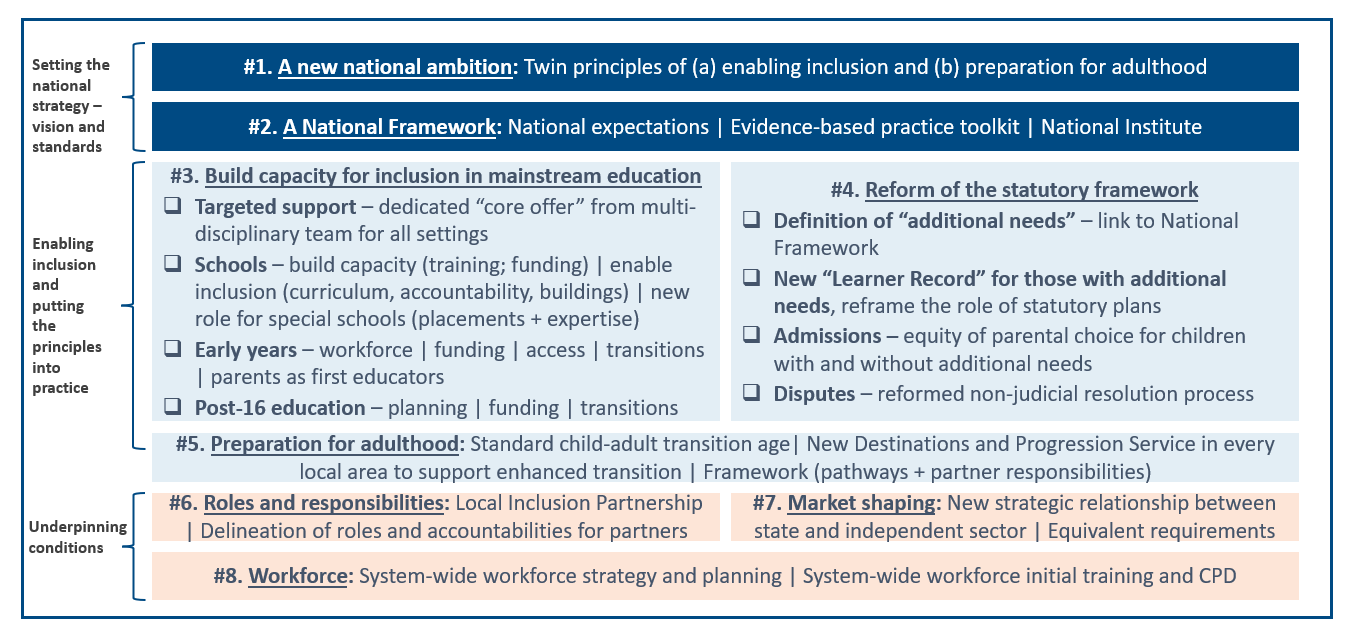

In our report, we recommend –

a new national ambition, championed by national government that can forge a sense of mission across government and unify the sector, based on twin principles of inclusion and preparation for adulthood;

a set of consistent national expectations of what we mean by additional needs and how those needs are to be met, which would provide a common rubric for talking about types and levels of needs, which in turn is a crucial prerequisite of consistent inclusive practice, and parental confidence, in mainstream education;

fundamental reform of mainstream education, from early years to schools to post-16, based on building capacity for universal and targeted support (e.g., access to key support services, increased funding and flexibility, support for the workforce), enabling and removing disincentives to inclusion, refocusing performance and accountability on inclusion, and improving strategic planning (especially in the early years and post-16);

reform of the current statutory framework (although this can only be done once greater system capacity for inclusion has been built) – retaining the principles that sat behind the 2014 SEND reforms (person-centred planning; co-production with young people, parents and carers), but reframing the statutory framework (the definition of additional needs, the role of statutory plans, disputes processes) to support an inclusive system rather than relying on a separate industry of individual entitlements as the only way to access much-needed support;

a new, dedicated, partnership-based approach to preparing for adulthood – aligning how different services support children as they move into early adulthood, setting out clear expectations of partners in children’s and adult services across education, health and care, and creating a new, dedicated local multi-agency service to support young people during the transition to adulthood;

putting local partnership working on a firmer foundation – creating a new, statutory Local Inclusion Partnership, with named statutory partners (including LA, health service, education sector, Parent Carer Forum and young people’s representatives), joint responsibilities, and a joint budget to shape local support;

defining a new, strategic role for the independent sector, with equivalent regulatory requirements and quality standards for all education settings offering state-funded placements for children and young people with additional needs (including a prohibition on profit-making); and

a whole-system workforce strategy, focused on ensuring that an inclusive education and childhood development system is recruiting, training and retaining a wide range of education, health and care practitioners.

The current SEND system is broken: it is adversarial, financially unsustainable, and is failing to prepare young people for adulthood. Our belief is that it is necessary to stop treating SEND as a separate “system” to the wider architecture of education and child development, and to replace this with an approach that places inclusion and preparation for adulthood at the heart of a more holistic, whole-system approach to education, child development and support for families. A new government offers a chance to reset and rebuild around a new national ambition for SEND. It will require considerable bravery and no little skill. As we have argued, however, reform is urgently needed and, ultimately, unavoidable.

We are grateful to those who contributed to this project: your perspectives have been instrumental in shaping our findings and we look forward to working together to test, develop and take forward our recommendations for change.